In an amusing after-dinner speech, recently delivered through an interpreter to the China Association, his Imperial Highness Duke Tsai Chi is reported to have said —

It

is well known that the mariner's compass was invented in China, and

to mention no greater results from its extended application in your

hands, one very happy result at any rate is that we have been safely

navigated to your hospitable shores. Gunpowder and guns had also

their origin in China. A very harmless beginning, and there it might

have stayed; but on the occasion of our recent visit to Woolwich

Arsenal we noticed how greatly our germ had developed; and the idea

suggested itself whether we had benefited mankind in making the

discovery.

Now no ordinary Chinaman would ever think of boasting that his countrymen invented either the compass or gunpowder and guns, for the simple reason that it would never occur to him that they had not invented them. He would certainly know nothing about the bitter controversy, waged entirely by foreigners, as to the proper allocation of the honours in question.

The Jesuit Fathers, de Mailla and Gaubil, of the 18th century, seem to have been satisfied that the compass was known to the Chinese in very early days, not only ages before it played any part in the civilisation of the West, but so far back as a thousand years and more before Christ. This position was hotly disputed by Dr. Legge in 1865, who concluded his note (Chinese Classics, V, p. 537) as follows: —

The truth, I imagine, is this, that the Chinese got some knowledge of the compass—found it out themselves, or learned it from India—not long before the Christian era, and that then the fables about the making of south-pointing chariots in more ancient times were invented.

He was backed up by Mayers in 1869 (Notes and Queries, iv, p. 11), who rashly and wrongly declared that Dr. Legge had

assembled the entire number of passages, occurring in ancient authors, which have given rise to the existing belief in the antiquity of this invention,

Neither was Mayers more happy in his

curious discovery respecting the probable date when the properties of the magnetic needle were in reality first observed in China—by Ma Kiün, a famous mechanician who flourished at the court of Ming Ti of the Wei dynasty, A.D. 227-239,—a brief notice of whom was met with by accident among the fragments of the works of Fu Tsze.

In 1891, Dr. Chalmers took a hand in the fray (China Review, xix, p. 52), opening his attack with the following words:—

Having long observed the intense desire the Chinese have to appropriate to themselves the invention of all sorts of things; and having once or twice already exposed the hollowness of their claims, as in the case of the 'striking clock' not regulated by a pendulum but by running water, I feel inclined to pity them when their long acknowledged claim to the early possession of the mariner's compass is called in question.

Dr. Chalmers goes on to say that he will give the facts of the case, leaving others to judge; but his note is eminently unsatisfying, as he only tells us in a vague way something of what the Chinese have said on the subject, and does not quote the ipsissima verba of native writers.

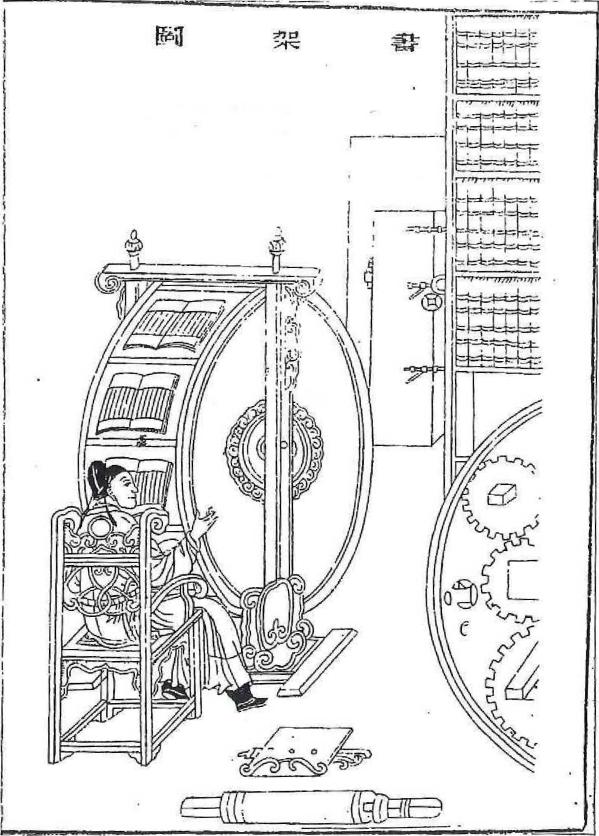

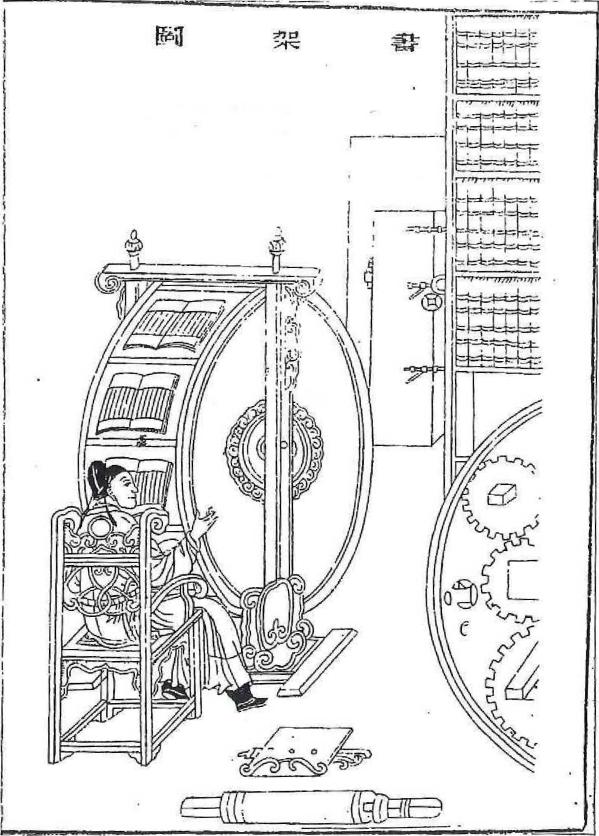

It is true that the Chinese have occasionally laid claim, and without any grounds, to purely western inventions; e. g. to the revolving reading-desk. Inspection, however, of the accompanying illustration will show that there are bound books in the bookcase, standing on end instead of lying, Chinese fashion, on their sides.

I now propose to omit all serious mention of the story, mistakenly said by Dr. Legge to be "given by Sze-ma Ts'-een", in which we are told that when the Yellow Emperor was enveloped in a mist by the first rebel, Ch’ih Yu, his legendary Majesty promptly invented the south-pointing chariot to guide himself and his army safely out of it, and finally succeeded in putting his rival to death. Also, to ignore the work known as the Ku chin chu, attributed to Ts`ni Pao of the 4th century A.D., on the ground that its genuineness is not beyond dispute, and to pass on to §18, p. 4 recto of the official History of the Sung Dynasty, A.D. 420-478, written by the well-known scholar and statesman Shên Yo, who lived A.D. 441-513. This authority is not even mentioned by either Legge, Mayers, or Chalmers; yet it contains a fairly full historical account of the whole matter, and its authenticity can in no way be impugned. It runs as follows:—

"The

south-pointing chariot was originally constructed by the Duke of Chou

(12th century B.C.), as a means of conducting homewards certain

envoys who had arrived from a great distance from beyond the

frontiers. The country to be traversed was a boundless flat, where

the envoys would be likely to lose their bearings; therefore the Duke

made for the first time this chariot, so that the envoys might always

be able to distinguish north from south.

The Philosopher of the Demon Gorge, a name given to Wang Hsü, 4th century B.C., states that the people of the Chêng State, when collecting jade, always carried with them a 'south-pointer', and were thus saved from going astray.

This seems to have been understood to mean that jade has itself the property of "pointing south" (see p. 113).

During the Ch’in and Western Han dynasties, however, nothing more was heard of this compass. Under the Eastern Han dynasty it was re-invented by Chang Hêng (A.D. 78 —139), but disappeared in the troubles amidst which the dynasty closed.

Kao T'ang-lung and Ch’in Lang of the Wei dynasty were both famous scholars.

The latter was a military commander. I can find no record of the former.

They disputed the point before the Court, saying, 'There is no such thing as a south-pointing chariot; the story is a fabrication.' The Emperor Ming Ti, during the Ch'ing-lung period (A.D. 233-237), gave orders to the Ma Chün to re-construct it, and the chariot was duly made, but was again lost during the troubles of the Chin dynasty. Shih Hu caused Hsieh Fei, and Yao Hsing caused Ling-hu Shêng, to make others.

Shih Hu was the successor, in A.D. 332, of Shih Lo, ruler of the Later Chao, one of the Sixteen States. Yao Hsing was ruler, from A.D. 394 to 416, of another State, the Western (or Later) Ch'in.

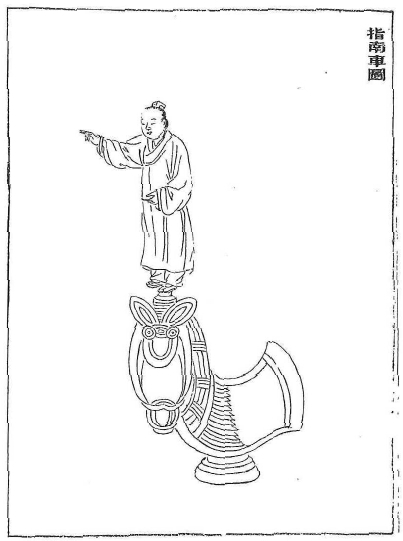

The Emperor An Ti in A.D. 417, and the Emperor Wu Ti of the Sung dynasty, when he settled Ch'ang-an, finally obtained this chariot. Its make was like that of a drum-chariot. A wooden figure of a man was fixed on the top, with an arm raised and pointing southwards, in such a way that although the chariot turned round, the arm still pointed south. This chariot, with the general impedimenta, went first, to lead the way.

The same chariot, as constructed by the western tribes (? Tibetans), did not work anything like so well; and although called a south-pointing chariot, very often did not point true, and had to be taken slowly round turns, as though dependent upon the help of man for its accuracy.

A man of Fan-yang, named Tsu Ch'ung-chih, who had an ingenious turn, often said that another chariot ought to be made.

Tsu Ch'ung-chih was a famous mathematical and mechanical genius, who died A.D. 500. "He constructed a machine which, not dependent on wind or water power, would revolve of itself, without any aid from man." Also a boat, which "would travel over 100 li a day,"—presumably by some mechanical means.

The Emperor Shun Ti, at the close of the Shêng-ming period (A.D. 477-479), when the Prince of Ch`i was his Minister, ordered him to make a chariot; and when completed, it was tested by Wang Sêng-ch’ien, Military Governor of Tan-yang, and by Liu Hsiu, President of the Censorate. Its workmanship was excellent, and although the chariot was twisted and turned in a hundred directions, the hand never failed to point south. Under the Chin dynasty there was also a south-pointing ship.

The former, A.D. 420-485, was an eminent statesman and calligraphist. On one occasion, the first Emperor of the Southern Ch’i dynasty, who greatly fancied himself as a calligraphist, challenged him to a trial of skill, and when they had finished, asked him whose was the best. "Mine is the best," replied Wang, "and your Majesty's is also the best," "Ah," said the Emperor with a laugh, "you know how to take care of your skin."

Toba Tao (third Emperor of the Northern Wei dynasty, died 452) caused an artificer named Kuo Shan-ming, to construct a south-pointing chariot, which was not completed in a year. There was also a man of Fu-fêng, named Ma Yo, who made one; and when he had completed it Kuo Shan-ming poisoned him."

The above account must be taken to represent all the available information from Chinese sources as to any early knowledge of the compass. Further mention of the famous chariot is made in later histories, such as those of the Wei, Northern Ch’i, and T’ang dynasties, as may be seen by reference to the P’ei wên yün fu; but I can find nothing therein of any particular interest. There is, however, one passage from the Shu chih hsü ching chuan biography of Hsü Ching in the History of the Shu Kingdom, written by Ch`ên Shou, A.D. 233-297, which may be worth quoting. It is this:—

You, sir, ought to take him as a compass (guide).

This figurative use of the term seems to presuppose the existence of something at any rate which was known to point invariably to the south. The Chinese idea as to what that was is shown in the annexed illustration, taken from the T’u shu chi ch’êng (A.D. 1726), where we are told that the figure of the man was 1.42 feet in height, and made of jade (see p. 110); also that the man stands on a swivel which is fitted through the head of Ch`ih Yu, the great rebel (see ante), —a motive constantly met with in Chinese decorative art. The writer declares that about A.D. 1317 he actually saw the chariot himself, and that the jade was slightly discoloured, apparently from age.

The Chinese have of course known the loadstone and its property from very early ages. It is mentioned in the Shan hai ching, —always to be quoted with reservations; also by Huai-nan Tzŭ of the 2nd century B.C., who says, "it will attract iron but not copper". In the San fu huang t’u, we read,—

The gateways of the Pleasaunce of O-fang (3rd cent. B.C.) were made of loadstone, so that anyone who was concealing weapons would be stopped.

In the I ko ts’ung ch’i lei su (quoted in the P’ei wên yün fu) we read:—

Not only is there a mutual attraction between likes, but also between unlikes; as for instance the loadstone, which attracts needles, and amber, which picks up snips.

The most important passage of all comes from the Méng ch'i pi t’an, by Shên Kua, A.D. 1030—1093, famous for his great learning, and also for his disastrous defeat by the Kitan Tartars. It runs a follows:—

Necromancers rub the point of a needle with the loadstone, and then it will point south.

Shên Kua lived, it will be noted, somewhere

about the time at which the compass appears to have first become

known to the Western world. Whether the Chinese were acquainted with

the magnetic needle before that date or not, the reader will now be

able to judge for himself.